AI-assisted cervical cancer diagnosis via a smartphone-enabled device

I was supporting EPFL’s EssentialTech Centre for a project in AI-assisted cervical cancer diagnosis during a three week development sprint. The centre’s mission is harnessing science and technology to drive sustainable development, support humanitarian action and foster peace. Considering that more than 80% of the global cervical cancer deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, coupled with the fact that the availability of doctors is low in many affected areas, the centre launched smartCervix.

Specifically, they developed an algorithm that can detect cervical cancer from images of the cervix. The benefit is that the procedure that could previously only be completed by doctors can – using the smartCervix application on a smartphone – also be undertaken by nurses and delivery nurses. Using smartphones to complete the procedure has several unique advantages such as an tapping into existing distribution channels for the hardware, while providing computing and networking capabilities at a low cost.

On the downside, however, smartphones are not medical devices and have a number of negative preconceptions in that context. In terms of form, smartphones are not adapted for use in medical examinations, in light of the number of requirements that medical professionals have in terms of maneouverability and usability. Secondly, smartphones are primarily conceived as communication devices, which becomes an obvious issue when it comes to taking photographs of highly private areas.

My involvement in the project was mostly in the field of industrial design to enable the smartphone to be used during the gynaecological procedure. In collaboration with an anthropologist that gathered insights from the user group, I created the PRD for an auxiliary enclosure and navigation jig for the smartphone. The main requirements were being able to quickly and efficiently move away and reposition the device, as the smartphone needs to be moved in and out of the operating field several times. Furthermore, based on patient interviews, it was clear that there was a clear expectation to be able to view the data collected, meaning the phone needs to be removable from the add-on device. Finally, due to the humanitarian nature of the project, the production cost should be low and the manufacturing method as low in complexity as possible. My design was then used for the first series of user testing with the MVP app.

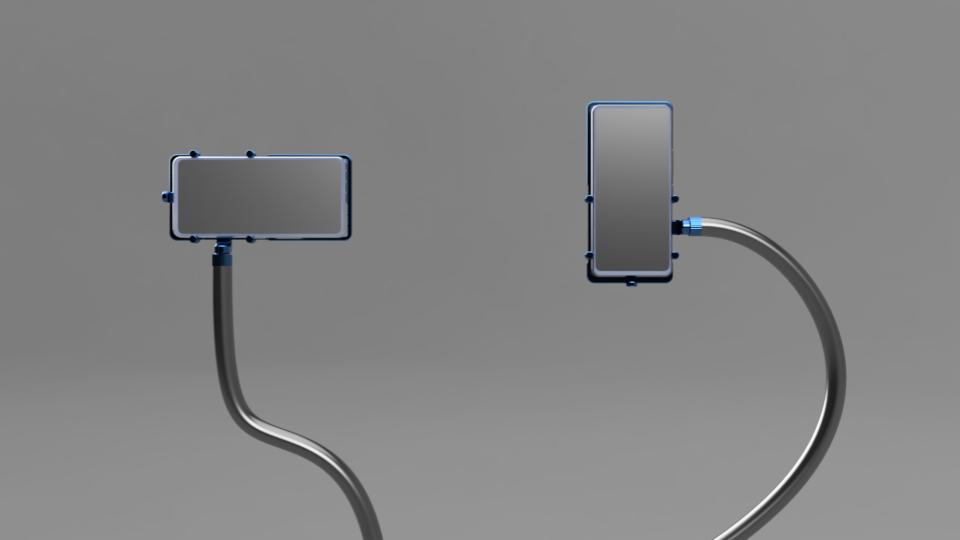

I designed a gooseneck system that offers full flexibility in terms of movement that can be mounted to an off-the-shelf tripod. In this way, the smartphone can easily be positioned correctly and with an additional degree of freedom be rotated in and out of view. The phone itself clamps into the enclosure thanks to a compliant mechanism built into the 3D print. The decision to go a single-part FDM print that can be attached to the gooseneck was largely made to keep manufacturing costs down.